Real People

Want to know more about one of the real people who appear in our books? They're all listed below.

- Elizabeth I

- Edward and Thomas Seymour

- Kat and John Ashley

- Thomas Parry

- William Paulet, Lord St John (Later Marquess of Winchester)

- Charles II

- Catharine of Braganza

- Barbara, Countess of Castlemaine

- Christopher Wren

- Isaac Newton

- Robert Hooke

- Robert Boyle

- John and Mary Evelyn

- John Locke

- Nell Gwyn

- Louise de Kéroualle, Duchess of Portsmouth

- Hortense Mancini, the Duchess Mazarin

- Henry Fuseli

- William Mulready

- James Northcote

- Sir Martin Archer Shee

- J.M.W. Turner

- Benjamin West

Elizabeth I (1533–1603)

Elizabeth I was one of England’s most beloved and longest reigning monarchs. She was the second child of Henry VIII and only child of Anne Boleyn. Henry and Anne fell in love while Henry was still married to Catherine of Aragon, his first wife and a devout Catholic queen. When the pope refused Henry permission to annul his marriage to Catherine, he broke with the Roman Catholic Church and established a brand new Anglican Church, of which he himself was head. He granted himself the annulment, married Anne, and made her his queen. Their daughter Elizabeth was born later the same year, and within three years Henry had tired of Anne and had her executed under trumped-up charges of adultery. He would go on to marry four more times and have one more child, the boy-king Edward VI.

Elizabeth as a young teenager, c. 1546

Elizabeth as a young teenager, c. 1546

Elizabeth grew up in and out of favor with her father and succession of stepmothers, alternately showered with affection and ignored. After her father’s death, her life grew even more tumultuous; Elizabeth’s nine-year-old brother became king and she was at first taken in by her final stepmother, Catherine Parr, and Catherine’s new husband Thomas Seymour. But rumors of a scandalous relationship between Elizabeth and Thomas soon drove Elizabeth from their home. She was able to set up her own establishment at Hatfield while her Protestant brother held the Crown, but when the boy died at age 15, Elizabeth’s Catholic older sister, Mary (known to history as Bloody Mary), became queen. Elizabeth spent the five years of her sister’s reign under intermittent arrest, threat of execution, and immense pressure to renounce her Protestantism. But Mary never could bring herself to get rid of her troublesome sister, and in 1558 she died leaving the throne to a 25-year-old Elizabeth.

Known as the Virgin Queen, Elizabeth never married—perhaps because of her early disastrous attachment to Thomas Seymour, because of what befell her mother, or simply because she had no wish to share the Crown. She reigned for forty-five storied years, skillfully seeing her country through an era of religious strife and military vulnerability, and is remembered as one of England’s great queens.

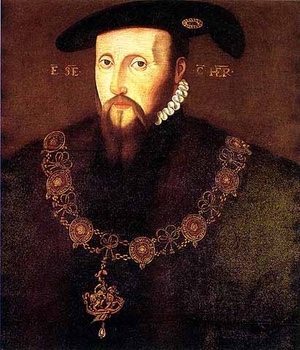

Edward and Thomas Seymour

Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset (1500-1552)

Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset (1500-1552)

Thomas Seymour, Baron of Sudeley (1508-1549)

Thomas Seymour, Baron of Sudeley (1508-1549)

Edward and Thomas Seymour were brothers to Jane Seymour, Henry VIII’s third and favorite wife (who died giving birth to baby Edward VI). When their sister became queen, the Seymour brothers were taken into King Henry’s inner circle, given titles and honors, and rose to prominence at court.

After Henry’s death, Edward Seymour parlayed his power into becoming Duke of Somerset and Lord Protector, the effective regent during his nephew Edward VI’s minority. Meanwhile, Thomas, the new Baron of Sudeley, grew jealous and engaged in many questionable activities with the aim of raising and financing a rebellion against his older brother. Thomas was executed for his crimes, and Edward followed his brother to the chopping block just a few years later, after his power waned and he was overthrown by his rival, the Earl of Warwick.

Kat and John Ashley

Kat Ashley (c. 1502–1565)

Kat Ashley (c. 1502–1565)

John Ashley (c. 1507–1595)

John Ashley (c. 1507–1595)

Born Katherine Champernowne, Kat’s parentage is uncertain and not much is known about her early life. She became a gentlewoman to the four-year-old princess Elizabeth in 1536, then a governess to the little girl the next year. Kat must have been well educated since she taught the princess mathematics, geography, astronomy, history, French, Italian, Flemish, and Spanish. In 1545 she married John Ashley, Elizabeth’s senior gentleman attendant and a cousin of Anne Boleyn.

When Elizabeth became queen in 1558, Kat was appointed First Lady of the Bedchamber while John became Master of the Jewel Office. She remained a close friend of the queen and influential leader of the aristocracy until her illness and death in 1565. John Ashley remarried and had six children by his second wife, Margaret Grey.

Thomas Parry (c. 1515–1560)

Thomas Parry was a cofferer (basically an accountant!) and favored member of the young Elizabeth I’s household. When she became queen in 1558, Parry was knighted and made a Privy Counsellor and Comptroller of the Queen’s Household. Though the queen was fond of him, Parry was not very popular at court and was said to have died of “mere ill-humour” in 1560.

William Paulet, Lord St. John (later Marquess of Winchester) (c. 1483–1572)

William Paulet led a long and distinguished career in government, beginning as High Sheriff of Hampshire in 1512 and rising to the highest national offices under four successive monarchs (Henry VIII and all three of his children, Edward VI, Mary I, and Elizabeth I). Paulet remained in favor with each crowned head despite their very different personalities and priorities—Queen Elizabeth once joked, “…if my lord treasurer were but a young man, I could find it in my heart to have him for a husband before any man in England." His career trajectory was helped along by what one might call a flexible attitude toward religion; Paulet professed various and sundry religious conversions as the Tudor monarchs vacillated between devout Catholicism, conservative Anglicanism, evangelical Protestantism, and finally, under Elizabeth I, tolerant Anglicanism. When asked how he survived and even thrived through all those years of religious upheaval, he said: "By being a willow, not an oak.”

Isaac Newton (1642–1727)

Appears in Sweet & Clean book The Viscount's Wallflower Bride

Isaac Newton was born on Christmas Day 1642 in the manor house of

Woolsthorpe in Lincolnshire. Newton came from a wealthy family of property

owners and farmers, but he never knew his father, who died three months

before he was born. He attended the Free Grammar School in Grantham, where

he was described as idle

and inattentive.

The headmaster

must have seen promise, though, because he convinced Newton's mother to

let him attend Trinity College in Cambridge.

While Newton is best known for discovering the Law of Gravity, he also created calculus, discovered that white light is composed of all the colors, and developed the three standard laws of motion that are still in use today. Despite these discoveries and more, it is said that he spent most of his time concentrating on alchemy experiments.

Newton was elected a fellow of the Royal Society in 1672, after donating a reflecting telescope. He was elected its president in 1703 and knighted in 1705. He died in 1727 and is buried in Westminster Abbey.

Robert Hooke (1635–1703)

Appears in Sweet & Clean book The Viscount's Wallflower Bride

Robert Hooke was born in 1635 on the Isle of Wight. The son of a priest, he attended school in Westminster and then Christ College, Oxford. At Oxford he was employed by Robert Boyle to construct an air pump. In 1660 he discovered Hooke's Law of Elasticity and is now considered the foremost mechanic of his time. His many inventions included a telegraph system, the spirit level, a marine barometer and sea gauge, and the balance spring, which made more accurate clocks possible.

In the year 1665, Hooke achieved worldwide scientific fame with the

publication of his book Micrographia, containing beautiful

drawings of objects he had studied through his self-built microscope. The

book also contains biological discoveries; for example, Hooke coined the

word cell.

Hooke was elected to the Royal Society in 1663 and became its curator for the rest of his life. He was Professor of Geometry at Gresham College, London, and lived there as a bachelor until his death in 1703.

The only known portrait of Robert Hooke, which hung in Gresham College, mysteriously disappeared shortly after his death. This is a picture of his memorial window in St. Helen's Bishopsgate, which, sadly, has since been destroyed.

Robert Boyle (1627–1691)

Appears in Sweet & Clean book The Viscount's Wallflower Bride

Born in County Waterford, Ireland, in 1627, Robert Boyle has been called

the Father of Modern Chemistry.

The youngest of fourteen children

of the wealthiest man in the British Isles, Boyle attended Eton and then

traveled the Continent with an older brother and a tutor, studying

philosophy, religion, languages, mathematics, and the new physics of

Bacon, Descartes, and Galileo. Unlike most scientists of his time, he was

more swayed by the new theories than by the alchemists.

In 1654, Boyle joined a small group of scientists, mathematicians, philosophers, and physicians who met weekly in Oxford and London. In 1662 the group was chartered as the Royal Society, with Boyle a founding member. That same year, he formulated Boyle's Law. He also developed the vacuum pump and is credited with being the first scientist to perform controlled experiments—a founder of the modern scientific method.

Boyle died in London in 1691, having never married. A man with deep religious convictions, he left most of his considerable estate to charitable organizations.

John and Mary Evelyn

Appears in Sweet & Clean book The Viscount's Wallflower Bride

Born in Surrey in 1620, John Evelyn is best known for his life-long diaries that have given us such a good picture of life in the 17th Century. Evelyn lived through the Civil War, the Commonwealth, the Restoration, the reigns of Charles II and James II, the Glorious Revolution of 1688, the reigns of William III and Mary II, and part of the reign of Anne—and he recorded it all.

Although a second son, Evelyn was born into an extremely wealthy family. He never wanted for anything and was known as a very critical and egotistical man. Along with his diary, he wrote some 300 other books. He declined all offices under the Commonwealth, but after the Restoration enjoyed great favor, received Court appointments, and was one of the founders of the Royal Society.

Mary Evelyn was the beloved only daughter of Sir Richard Browne, Charles I's ambassador to Paris. Raised in France, she was highly educated and married reluctantly to Evelyn in 1647, at the age of only thirteen, when he was in Paris with King Charles II's exiled Court. Evelyn was twice her age, and although his diaries reveal that he loved her, he treated her rather parentally. He allowed her to continue her studies, but insisted that housekeeping should have first priority over everything else in her life.

It was a man named Ralph Bohun, her son's tutor, who first encouraged Mary

to take up scientific experimentation in her still-room. A supportive

cousin and her brother-in-law both sent her supplies, and the resulting

receipts

(recipes) survive in the Evelyn's household receipt book.

After spending six years in their home, Bohun returned to Oxford, but he

and Mary kept up a lifetime correspondence, and he shared her letters and

observations with the great men of Oxford and the Royal Society. Although

she was denied public participation in intellectual life, through Bohun

she was able to maintain links with it.

John Evelyn died in 1706 and Mary three years later. They were both buried in Wotton church, where in 1992 their tombs were broken into and their skulls stolen. The tragic mystery of why or how has yet to be solved.

John Locke (1632–1704)

Appears in Sweet & Clean book The Viscount's Wallflower Bride

John Locke was born in Somerset in 1632, to the son of a captain of horse in the parliamentary army. The Civil War does not seem to have disrupted his education, as he entered Westminster School in London in 1646 and Christ Church, Oxford in 1652. The official studies of the university were not congenial to him; he preferred Descartes' philosophy to Aristotle's. But nonetheless he persevered and eventually earned a degree as a doctor of medicine.

Locke was elected a fellow of the Royal Society in 1668. In later life he published many works on philosophy, politics, theology and economics, including Essay concerning Human Understanding, Two Treastises on Government, Letters on Toleration, and Some Thoughts concerning Education. He helped to form contemporary ideas of liberal democracy and greatly influenced American politics.

Locke postulated that all governments derive their authority from popular

consent (a contract with the people), so that government may be rightly

overthrown if it infringes on such fundamental rights of the people as

religious freedom. He believed that at birth the mind is a blank, and that

all ideas come from sense impressions. He believed strongly in religious

toleration and argued for a separation between church and state. Thomas

Jefferson called Locke one of the three greatest men that have ever

lived, without any exception,

and drew heavily on his writings in

drafting the Declaration of Independence.

During the last eight years of his life, Locke became severely asthmatic and couldn't bear the smoke of London. He retired to Essex where he died in 1704 at the age of 72.

Nell Gwyn (1650–1687)

Appears in Sweet & Clean book The Gentleman's Scandalous Bride

Never in English history has another Royal mistress been as popular as

pretty, witty

Nell Gwyn. Whether Nell was actually born in a

brothel is open to question, but legend has it she came into the world in

Drury Lane in February, 1650. As a young girl, Nell sold oranges at the

Theatre Royal and began as an actress there in 1665. Charles II saw her on

stage, and by 1668 she became his mistress. Nell bore the King two sons,

Charles in 1670, later the Duke of St. Albans, and James in 1671. Nell was

quite possibly the only one of Charles's mistresses who actually loved

him, and he never tired of her. On his deathbed, his last request to his

brother (James II) is said to have been let not poor Nelly starve.

Louise de Kéroualle, Duchess of Portsmouth (1649–1734)

Appears in Sweet & Clean book The Gentleman's Scandalous Bride

Of all Charles II's mistresses, Louise de Kéroualle was most

disliked. Born in 1649 in France, Louise first came to England in 1670 as

a maid of honor to Charles's sister, Henrietta. Charles's interest was

apparent, and when Henrietta died later that year, Louise returned to

London and was established as the King's mistress, receiving Louis XIV's

congratulations on her success. After giving birth in 1672 to another of

Charles's sons named Charles, later the Duke of Richmond, she was created

the Duchess of Portsmouth. Though Louise's unpopularity was due mostly to

her being French and Catholic, she was also known to be wildly extravagant

with the King's money. Her apartments at Whitehall were rebuilt three

times, and John Evelyn said they had ten times the richness and glory

beyond the Queen's.

Hortense Mancini, the Duchess Mazarin (1646–1699)

Appears in Sweet & Clean book The Gentleman's Scandalous Bride

Hortense Mancini, the Duchess Mazarin, was one of five Italian sisters all

noted for their great beauty. Two of them became mistress to Louis XIV.

Born in Rome in 1646, Hortense moved to France at an early age. Charles II

proposed to her while there, but her uncle, Cardinal Mazarin, did not

think the exiled king's prospects were good. She later married and then

left her husband, arriving at Charles's Court in 1675 and becoming his

mistress shortly thereafter. Considered an adventuress,

she was

known for her compulsive gambling, her great skill with guns and swords,

and her inclination to wear men's clothing.

Henry Fuseli (1741–1825)

Appears in Sweet & Clean book How I Spent My London Season

The son of a portrait painter, Henry Fuseli was born in Switzerland and trained in theology as well as art and art history. He moved to England at the age of 23, and then, encouraged by Sir Joshua Reynolds, went to Italy to study for eight years. Upon his return to London, his works exhibited at the Royal Academy secured his reputation. His subject matter was mainly literary, and his most famous works, such as The Nightmare, featured macabre fantasies and often erotic or grotesque images. He was elected a full Academician in 1790 and taught painting at the Academy from 1799-1805.

Quote: Our ideas are the offspring of our senses.

Henry Fuseli's The Nightmare.

Henry Fuseli's The Nightmare.

William Mulready (1786–1863)

Appears in Sweet & Clean book How I Spent My London Season

The son of a leather breeches maker, William Mulready moved from Ireland to London at the age of five, and at fourteen he was admitted to the Royal Academy schools. His early works were historical paintings and landscapes, but later works inspired by the seventeenth century Dutch masters won him critical acclaim. Mulready married Elizabeth Varley, a landscape painter, and they had four sons, two of whom went on to be painters themselves. Mulready was elected a full Academician in 1816.

William Mulready's The Fight Interrupted, shown in the Summer

Exhibition of 1816.

William Mulready's The Fight Interrupted, shown in the Summer

Exhibition of 1816.

James Northcote (1746–1831)

Appears in Sweet & Clean book How I Spent My London Season

Born and raised in Plymouth, James Northcote was apprenticed to his father, a poor watchmaker, but drew and painted in his spare time. At age 23, he left his family and set himself up as a portrait painter. Four years later, he moved to London, where Sir Joshua Reynolds accepted him as a student and assistant. At the same time, he attended the Royal Academy schools. When his formal training ended, he traveled to Rome for three years, then returned and established himself as a painter of history scenes and portraits. Elected a full Academician in 1787, his works eventually numbered about two thousand, which made him a fortune of £40,000. Northcote also sought fame as an author, publishing the popular biographies Life of Reynolds and Life of Titian.

Quote: Half the things that people do not succeed in are through fear of

making the attempt.

James Northcote's painting, depicting the last scene of Romeo & Juliet.

James Northcote's painting, depicting the last scene of Romeo & Juliet.

Sir Martin Archer Shee (1769–1850)

Appears in Sweet & Clean book How I Spent My London Season

Sir Martin Archer Shee's father, a wealthy merchant from an old Irish family, thought painting an unsuitable occupation for his son. Nevertheless, Shee studied art in the Dublin Society and then made his way to London, where Joshua Reynolds suggested he study at the Royal Academy. Principally a portrait painter, he was popular in court and theatrical circles and won many royal commissions. Shee was elected an Academician in 1800 and served as its president from 1830 until his death in 1850.

Portrait of William Roscoe by Sir Martin Archer Shee.

Portrait of William Roscoe by Sir Martin Archer Shee.

J.M.W. Turner (1775–1851)

Appears in Sweet & Clean book How I Spent My London Season

Self-portrait of J.M.W. Turner.

Self-portrait of J.M.W. Turner.

Joseph Mallord William Turner was born in Covent Garden, London, to a barber and wig-maker father and a mentally ill mother. Because of his mother's instability, he was sent to live with an uncle, but his father displayed his young son's pictures in his shop window. Turner entered the Royal Academy of Art schools in 1789, when he was only 14 years old. Sir Joshua Reynolds, president of the Royal Academy at the time, chaired the panel that admitted him. One of Turner's watercolors was accepted for the Summer Exhibition of 1790 after only a single year's study. He exhibited his first oil painting in 1796 and continued exhibiting at the Summer Exhibition nearly every year for the rest of his life. He was elected a full Academician at the age of 29.

Although best known for his oils, Turner was also a great master of

watercolor landscape painting. He is commonly known as the painter of

light,

and it is claimed his style laid the foundation for Impressionism.

Upon his death, Turner was buried in St Paul's Cathedral at his request,

where he lies next to Sir Joshua Reynolds.

The Fighting Téméraire by J. M. W. Turner, 1838.

The Fighting Téméraire by J. M. W. Turner, 1838.

Benjamin West (1738–1820)

Appears in Sweet & Clean book How I Spent My London Season

Self-portrait of Benjamin West.

Self-portrait of Benjamin West.

A founder of the Royal Academy when it was formed in 1768, Benjamin West was

born in the United States, the tenth child of an innkeeper. He taught himself

painting in his hometown of Philadelphia, where he claimed Native Americans

showed him how to make paint by mixing some clay from the river bank with bear

grease in a pot. As a young man, he established himself as a portraitist in

New York City before leaving for Europe. At the age of 22, he sailed to Italy

and traveled to most of its art centers over a three-year period, then settled

in London. After catching the eye and patronage of King George III, he no

longer needed to paint portraits for a living, and instead became acclaimed for

his large scale historical paintings. In these paintings, which he termed

epic representation,

he clothed his figures in the costume of their

period rather than traditional classical garb. Although this was controversial

at first, it eventually won him great fame and popularity.

West served as the Royal Academy's president from 1792 to 1805 and again from 1806 until his death in 1820. He was a close friend of Benjamin Franklin, and Franklin was the godfather of his second son. Although West never returned to the United States, his work had considerable influence on U.S. art in the 19th century.

Benjamin West's The Death of Nelson, 1806.

Benjamin West's The Death of Nelson, 1806.